From Surf Anthems to Sonic Genius: The Untold Psychedelic Struggles & Triumphs of Brian Wilson – How One Tormented Beach Boy Redefined Pop Music Forever Against All Odds

Wilson called himself ‘psychedelicate’; his brother Dennis said Brian ‘is the Beach Boys. He is all of it. We’re nothing. He’s everything’

Brian Wilson, best known as one of the Beach Boys, who has died aged 82, was a brilliant writer of evocative songs about the surf who later became beset by emotional problems which kept him in bed for almost a decade.

In the early 1960s, before and after The Beatles’ arrival, Wilson, together with his brothers, a cousin and a shifting band of cohorts, had hits around the world with songs redolent of that era when T-Birds cruised beneath an endless summer sun.

California Girls, Help Me, Rhonda, Surfin’ Safari, I Get Around and Fun, Fun, Fun led to the experiments of Pet Sounds (1966), the band’s highly influential 11th studio album, which contained God Only Knows and a version of Sloop John B. Then came a putative masterpiece, Smile, which only saw fragmentary light of day, notably in their best song, Heroes and Villains; the chaos of the LP’s conception and creation, belying its title, harbingered the decades of agony and feuding, something to which the brothers’ upbringing had accustomed them.

Brian Douglas Wilson was born in Inglewood, California, on June 20 1942. His father, Murry Wilson, was an unsuccessful songwriter of uneasy temperament (he had lost part of an ear from a blow from his own father) who would remove his glass eye in front of his impressionable son and require him to defecate on a newspaper in front of him. Audree Wilson, his mother, was an alcoholic. “I had a good childhood,” Wilson later told an interviewer, “except for my dad beating me up all the time.”

Despite the tense atmosphere, music filled the house, and young Brian’s deafness in one ear – rumoured to have been the result of an early beating by his father, although Wilson later said that he had been hit over the head by a local teenager – proved no handicap when it came to performing and writing himself.

It was at the age of two, when visiting his grandmother, that he first heard Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. The effect was profound, he recalled: “I still hear every emotion I’ve ever experienced in that piece.”

His first song, worked out at the age of five on an out-of-tune ukelele, brought a paternal warning of what would happen if he did not go back to bed: “I’m gonna splinter that thing across your ass.” Music, though, was to provide the harmony which was otherwise lacking in his life. It became as necessary to him as sleeping and eating, both activities which, in time, were to dominate his days when music had brought him riches.

The road to success can be dated from the afternoon when, aged 14, he was being driven by his mother with his brothers, Dennis and Carl, and a song by the Four Freshmen came on the wireless. He was transfixed, and later that week did nothing outside school but listen to their LP The Four Freshmen and Five Trombones.

He attempted to create similar vocal harmonies with his family, and on his 16th birthday was given a tape-recorder, which he “used like a science kit”. By now were added to the influence of the Four Freshmen such grittier singers as Johnny Otis and Little Richard. For part of his course-work at high school he was obliged to write a sonata, but turned in a pop song, Surfin’.

Joined by the Wilsons’ cousin, Mike Love, and a school friend, Al Jardine, the prototype group was formed, with Murry Wilson as their manager.

Love called the group the Pendletones (after a brand of shirt) and, as chance had it, an offer came up to sing Sloop John B. But their effort did not impress the record label, who asked whether the group had anything else.

Dennis Wilson – the only member of the band who actually surfed – startled the others by mentioning Surfin’, which was, as yet, unfinished. The label’s amiable interest was sufficient to galvanise Wilson into arranging it for the group at home. The tapes of the sessions which resulted in Surfin’ vanished for more than 30 years. On them can be heard the evolution of the harmonies which the Wilsons brought to a Chuck Berry-like rhythm.

The group’s delight at seeing the single itself was as great as their surprise at the name printed on it. Without being told by the distributor, they had become the Beach Boys.

Wilson was philosophical: “We had a record out. That was a considerable achievement by itself, far more important than a silly name.”

Surfin’ was a local hit, the group played concerts, and the record broached the national chart, although the Beach Boys saw little money from it. More songs quickly followed.

The first of several people with whom Wilson collaborated was Gary Usher. The pair averaged a song a day, hymning the hobbies of the coast: 409 described a motor-car, adolescent angst filled In My Room, while the Pacific continued to make its presence felt in Surfer Girl and Surfin’ Safari.

The success of these paeans to pleasure fuelled acrimony with Wilson’s father, who was eager that more and more of the publishing rights should be made over to him. Wilson left home, determined to match the full sound achieved by Phil Spector even on such early records as He’s Sure the Boy I Love.

He began collaborating with Roger Christian. Little Deuce Coupe and Shut Down were among their first songs, while the opening line of Surf City summed up the era: “Two girls for every boy!” In 1963 this became Wilson’s first No 1, and that same year Surfin’ USA peaked at No 2.

But Wilson took little pleasure in touring, which he found boring and repetitive, and he wanted to be in the studio as much as possible. His first experiments as a producer were with Betty Everett and, using Spector’s musicians, a group formed of his girlfriend (who became his wife), Marilyn Rovell, her sister and her cousin (for a while, Wilson shared a curiously innocent bedroom with both sisters).

None of these was a hit, but Wilson became as much a driven force as Spector, unable to rest but wanting to get on vinyl the sounds that he heard in his head. Songs continued to flow, often without a collaborator, which soured relations with his cousin Mike Love, who had an eye on the money they brought him.

All the while Brian’s father needled and pressured him – so much so that during a problematic session for I Get Around Wilson finally pushed him across the room and said that he was fired as manager. The song, meanwhile, proved to be the group’s first No 1, something all the more welcome in the face of competition from The Beatles. But by now Wilson was beginning to experiment with drugs.

In two years he had written and produced eight LPs, and his exhaustion was compounded by the thought of trying to compete with the latest Spector production, the Righteous Brothers’ You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’. (It is a curious footnote to musical history that Wilson was asked to play piano on one track of Spector’s celebrated Christmas LP but was no match for Leon Russell, while their only collaboration ended up being given to a public-service station as a commercial for the unemployed, redubbed by Jay and the Americans.)

He had a breakdown from which he recovered sufficiently quickly to produce the LP which Capitol, on to a good thing, was demanding. He belatedly realised that quirks of behaviour could be turned to his advantage, for he was the one delivering these goods, the latest being another No 1, Help Me, Rhonda, which began as a doodle inspired by Bobby Darin’s version of Mack the Knife.

He told the others that while they toured, he would stay and make the records (among the substitutes for Wilson on the road was Glen Campbell, then one of Spector’s guitarists before turning his falsetto to account in his own right, beginning with a little-known Wilson song, Guess I’m Dumb). Wilson’s work, meanwhile, fuelled by drugs, took a change of direction: slower, introspective songs such as Please Let Me Wonder pointed the direction to Pet Sounds.

In the aftermath of his first acid trip he wrote the beautifully sunny and carefree California Girls. That night, Wilson would recall, was the first time he heard a threatening voice in his head that would stay with him for many years. The song was recorded with Spector’s musicians in place of the Beach Boys.

Wilson’s confusion, now in part a fixation upon Marilyn’s sister, did not ease up, but amid this the group itself recorded a spirited party album which yielded a hit version of a song suggested on the spur of the moment, the Regents’ old Barbara Ann.

With the group away again (his brother Dennis drawn as much by the prospect of women as anything), Wilson meandered through such woolly philosophy as the I Ching, and then heard The Beatles’ LP Rubber Soul which, containing the likes of Norwegian Wood, marked a distinct change from such records as She Loves You.

Wilson had to match this. The way in which he did so began in an unlikely fashion, with a version of the song which had failed to launch the group upon a career. This time Sloop John B was given a dynamic arrangement which the others’ voices did not suit, so Wilson overdubbed himself repeatedly. He evolved tunes and “feels” of his own, and brought in as a lyricist and collaborator Tony Asher, a copywriter who had visited the studio a few months before. The result was the boldly futuristic Pet Sounds, which is frequently cited as the first concept album in rock music, on which Wilson’s experiments with melody, themes and instruments can be heard in tracks such as Caroline No, Wouldn’t It Be Nice, God Only Knows and Don’t Cry (Put Your Head on My Shoulder).

Capitol’s lack of enthusiasm meant that the LP did not have the chance to match earlier sales. A “Best Of” compilation overtook it, but Pet Sounds, inspired by the Beatles, determined Paul McCartney upon the idea of Sgt Pepper (both LPs end with noises for the benefit of dogs).

Wilson briefly wondered what he might do next, but left off the LP was a song inspired by his mother’s remarking that dogs can sense bad and good vibrations. Recorded piecemeal-fashion – nobody was quite certain what it meant and how on earth it would do – the quivering and quavering masterpiece Good Vibrations (1966) confounded Love’s view that it was “avant-garde crap and too long” by selling 100,000 a day and becoming their biggest (Love had to learn to play it on tour). Fearful that it might have gone the way of Spector’s epic River Deep, Mountain High and sunk without trace in America, Wilson felt emboldened to undertake an LP that would deliberately create a picture of America in both myth and fact.

This was to be Smile, and for this, another stray lyricist, Van Dyke Parks, was brought in. In an effort to recapture lost spirit, Wilson set up a piano in a sandbox. His dogs promptly relieved themselves in it. Smile was abandoned in 1967, although the group was to have no finer moment than one of its tracks, Heroes and Villains, which began with Parks’s lyrics: “I’ve been in this town so long that back in the city I been taken for lost and gone and unknown…”

The surviving songs emerged over the years in one form or another but the others – and the concept – remained beyond the grasp of Wilson, who was by now waylaid by his fragile mental health and the drugs from which a bunch of hangers-on would hardly persuade him to desist. Smile was eventually issued in 2011, when it received a Grammy Award for Best Historical Album.

For most of the next two decades, Wilson’s life was dominated by depression and drugs. The wonder is that he survived (he later described himself in an interview as “psychedelicate”). Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s he made countless home demo recordings, later referred to as the “Bedroom Tapes”. Most of these remain unreleased.

In 1969 he opened a health food store called The Radiant Radish, but the business folded after a couple of years. He became paranoid over Spector, even under the delusion that he had produced a film with the specific intention of terrorising him. An even more surreal note was added to this period by Capitol’s issuing an LP called The Many Moods of Murry Wilson; it sold so poorly that it is now a collectors’ item. Wilson père, meanwhile, continued to taunt his son while demanding a share of his fortune.

Wilson’s spirit was summed up in one of the few songs that he now gave the group, Busy Doin’ Nothing. Having moved on from marijuana and LSD to cocaine, he was abetted in his lassitude with drugs supplied by Danny Hutton, a one-time protégé who became a part of Three Dog Night – best-known for a version of Randy Newman’s Mama Told Me Not to Come. Meanwhile Wilson’s brother Dennis had become embroiled, almost to the point of disaster, with the commune run by Charles Manson.

The Beach Boys attempted a comeback with a single, Break Away, co-written by Wilson and the father from whom he was never able to free himself. Fattened by junk food, forever with Hutton, Wilson was risking the loss of wife and children and was so far gone that he imagined that a fairy-tale, “Mount Vernon and Fairway” (included as a single with the Holland LP) was a creative peak, and was enraged that the others reworked a Smile fragment as the title-track of Surf’s Up. Amid this, Murry Wilson died. But it would take more than that to release his son.

With such an aim in mind, in 1975 Wilson’s wife Marilyn sought help from the psychologist and psychotherapist Dr Eugene Landy, an involvement which was to be as controversial as any in Wilson’s life. Reluctantly, and then enthusiastically, Wilson agreed to treatment, which soon led to Landy managing his life from dawn until dusk.

During the recording of the passable 15 Big Ones (1976), Landy supervised meetings and was even brought in by Wilson as a writing partner. Landy also arranged for Wilson to appear on Saturday Night Live, where he gave a solo piano performance of Good Vibrations while his therapist stood off-camera holding up signs saying “smile”.

But by the end of 1976, after Landy had doubled his fees, Stan Love, Wilson’s cousin and manager, fired him. Wilson remained fragile, however, and even more vulnerable now that his brothers Carl and Dennis were heavily into drugs and, unknown to Wilson, had struck a new recording deal stipulating that he write and produce 80 per cent of the material.

By 1978 Wilson and Marilyn had separated, the latest LP was another flop and he was a wreck, even sleeping on the floor of the stage during one concert. Years went by that in retrospect were little more than a blur. In 1982 he almost died (one firm took bets on it, some rumoured).

Again, Marilyn (from whom he was divorced) called in Dr Landy. Agreement reached all round, Landy organised a new regime with a precision similar to that of a military manoeuvre. Wilson was taken by him to an isolated part of Hawaii at the beginning of 1983 and there underwent the psychiatric equivalent of national service. Several months’ stay had him sufficiently recovered to join the group on stage, rearranging I Get Around on the spot and then returning to Los Angeles, a risk, but one which he survived, even fending off his brother Dennis’s request for money to buy drugs.

But in November 1983, Dennis, whose alcoholism and drug dependency had left him homeless and living a nomadic existence, drowned, following a day of drinking, at Marina Del Rey.

Again, Wilson was drawn into the group, Landy ever-present, to their irritation. Between 1983 and 1986, Landy charged Wilson approximately $430,000 a year and received 25 per cent of the copyright to all of Wilson’s songs, whether or not he had any involvement in writing them. In 1987 Landy and Wilson set up a company called Brains and Genius, from which each of them would share profits from any recordings, films, soundtracks, or books. The following year Landy was credited as the co-writer and executive producer for Wilson’s solo album, Brian Wilson.

In 1986 Wilson had met his future wife and manager, Melinda Ledbetter, when he went to look around the Cadillac dealership where she was working. Soon after, she reported Landy to the state (after which Landy attempted to discourage her relationship with Wilson), and in February 1988 the State of California Board of Medical Quality charged Landy with the improper prescribing of drugs and unprofessional relationships with patients, including Wilson’s psychological dependency on him.

Although Landy was told to surrender his licence for two years, he still retained his influence over Wilson. But after discovering that Landy had been named as chief beneficiary of Wilson’s will in 1989, the Wilson family contested his control over Wilson, which resulted in 1992 in a court order barring Landy from contacting him.

In his autobiography, I am Brian Wilson (2016) – which superseded Wouldn’t It Be Nice: My Own Story (1991), written under Landy’s influence and dedicated to him – Wilson gave a typically laconic and understated assessment of their years together: “When Dr Landy left, he left me to my freedom. I can’t say that I knew what to do with it right away.”

With the support of Melinda, Wilson began slowly to emerge from his dependency on Landy and the huge quantities of drugs he had been prescribed. In 1995 he released two more albums and went on to record The Wilsons (1997) with Carnie and Wendy Wilson, the daughters from his first marriage.

During the mid-1990s he made a few recordings with the Beach Boys and began to face his stage fright in some live performances with the group. This was followed, in 1998, by Imagination, an album for which he had vocal coaching and help with stage fright. Despite the fact that Wilson and his wife subsequently fell out with the album’s producer, Joe Thomas (resulting in yet more legal wrangling), the album was, as Wilson recalled in his autobiography, “a great experience in other ways. It got me making music again. It got me back on the road.”

Another solo album, Gettin’ In Over My Head (2004), included collaborations with Elton John, Paul McCartney and Eric Clapton and his brother Carl, who had died of lung cancer in 1998. Twenty years later Wilson would say that his lowest moments were usually when he thought about how much he missed his brothers.

In 2004, after working further on the shelved Smile album, Wilson toured Britain before releasing Brian Wilson Presents Smile later that year. In June 2005 he performed at the Glastonbury Festival. Several months later his former bandmate Love sued Wilson, accusing him of “shamelessly misappropriating” Love’s songs, the Beach Boys trademark and the Smile album. The lawsuit was dismissed.

“Brian Wilson is the Beach Boys,” Dennis Wilson, who throughout his life remained unfailingly loyal to his brother, had once said. “He is the band. We’re his f—ing messengers. He is all of it. Period. We’re nothing. He’s everything.”

In 2014 Love & Mercy, a biographical film about Wilson’s life, was released. The following year he made his 11th solo album, No Pier Pressure.

I Am Brian Wilson, the second memoir, was dedicated to his second wife Melinda with the words: “God only knows what I’d be without you.”

“Have I stayed strong?” wrote Wilson. “I like to think so. But the only thing I know for sure is that I have stayed.”

In 2021 he released At My Piano, solo versions of Beach Boys classics, and he toured that year and in 2022.

But in 2024, a few months after the death of his wife Melinda, Wilson was placed under a conservatorship, overseen by his publicist Jean Sievers and manager LeeAnn Hard, because of what his doctor called a “major neurocognitive disorder”.

He is survived by two daughters from his first marriage, and three adopted daughters and two adopted sons from his second marriage.

News

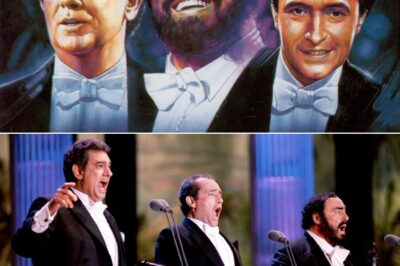

When José Carreras stepped onto the stage to perform Torna a Surriento in honor of Mario Lanza, no one expected what would unfold next—his voice didn’t just fill the room; it seemed to reach back through time, echoing with the passion and brilliance of a forgotten era. The atmosphere shifted, the audience fell silent, and some even questioned if they were witnessing more than just a performance. Was this truly Carreras, or had the very soul of Neapolitan music been awakened through him? What mysterious force stirred that night? Why did this single performance leave even seasoned opera lovers speechless? One thing was certain: something unforgettable happened—and it may never happen again.

When José Carreras performed Torna a Surriento in his tribute to Mario Lanza, it was as if the spirit of…

“There’s a Musical Performance Everyone Keeps Talking About, and It’s Not What You Expect—André Rieu’s Rendition of ‘Ballade Pour Adeline’ Has Left Millions Puzzled, Captivated, and Compelled to Rewatch Without Understanding Why—Some Call It a Perfect Mystery in Sound, Others Say It’s Just a Simple Tune, Yet It Continues to Spread Globally with Unexplainable Force—What Is It About This Instrumental That Pulls People In So Deeply? Why Are Listeners Around the World Experiencing Something They Can’t Explain Whenever This Version Plays? One Thing Is Certain: Whether You’ve Heard It Before or Not, There’s Something Hidden in This Performance That Might Change How You Experience Music Forever.

“There’s a Musical Performance Everyone Keeps Talking About, and It’s Not What You Expect—André Rieu’s Rendition of ‘Ballade Pour Adeline’…

You’ve Heard the Voice… But Do You Know the Man Behind It? From Frozen Beginnings in Siberia to Standing Ovations Across the Globe, Dmitri Hvorostovsky Uncovers the Untold Chapters of His Rise to Fame—A Journey Marked by Unimaginable Highs, Quiet Struggles, and Personal Discoveries Never Shared Until Now in This Rare and Candid Sit-Down with Bing & Dennis That Will Leave You Reexamining Everything You Thought You Knew About the World’s Most Captivating Baritone

You’ve Heard the Voice… But Do You Know the Man Behind It? From Frozen Beginnings in Siberia to Standing Ovations…

The moment classical music hijacked a disco legend—watch as Rieu’s strings unleash a tidal wave of joy, turning solemn concert halls into dancing riots. This isn’t just crossover; it’s a revolution where bow meets bassline, and the audience loses all restraint. Proof that even the grandest stages can’t contain the explosive power of a timeless anthem reborn.

The moment classical music hijacked a disco legend—watch as Rieu’s strings unleash a tidal wave of joy, turning solemn concert…

The Note That Shattered Eternity: Pavarotti’s Forbidden Rise from Obscurity to Opera’s Unrivaled Throne—A Documentary That Uncovers the Raw Truth Behind the Legend. How One Man’s Voice Defied Gravity, Broke Every Rule, and Rewrote Music History. Secrets, Scandals, and the Untold Sacrifices That Built an Icon. This Isn’t Just a Film—It’s a Revelation That Will Leave You Breathless. Witness the Explosive Journey of the Century, Where Talent Collided with Destiny, and the World Still Hasn’t Recovered. For Fans Who Think They Know Everything and Newcomers Who Dare to Discover: Prepare for the Unthinkable.

The Note That Shattered Eternity: Pavarotti’s Forbidden Rise from Obscurity to Opera’s Unrivaled Throne—A Documentary That Uncovers the Raw Truth…

Andrea Bocelli and Veronica Berti’s Breathtaking Duet: A Romantic Symphony of Love, Dance, and Passion That Captivated the World – Their Eyes Locked, Voices Merged, and Hearts Spoke in a Moment So Pure, It Felt Like Time Stood Still. Witness the Magic of Their Unbreakable Bond, the Grace of Their Waltz, and the Fire of Their Final Kiss That Left Millions Spellbound. This Isn’t Just a Performance—It’s a Love Letter Set to Music, a Testament to Devotion That Redefines Fairytale Romance. Every Glance, Every Note, Every Step Tells a Story of Two Souls Perfectly in Sync. Prepare to Be Moved Beyond Words!

Andrea Bocelli and Veronica Berti’s Breathtaking Duet: A Romantic Symphony of Love, Dance, and Passion That Captivated the World –…

End of content

No more pages to load